Our law school has a writing seminar titled Transnational Class Actions. A good number of questions come to me as the FCIL librarian from students in the seminar who are looking for reference assistance of various kinds. This semester questions have come from students looking for potential paper topics and for cases on point. This raises the question of how much the librarian should know substantively about a subject in order to provide reference assistance. In the course of several years of providing library support to the Transnational Class Actions seminar, including collection development, I have learned enough about the field to, for example, suggest some paper topics or steer students to cases on point. On the theory that questions dealing with the subject could arise in the work of other FCIL librarians, this post is devoted to some of the lessons learned about providing reference assistance on the subject.

The field of transnational class actions divides into two main categories. On the one hand, there is the U.S. class action that has transnational elements. On the other hand, there is the equivalent of the class action in other countries. These often do not have the name class action; they could be called group actions, collective actions or representative actions.

One of the outstanding transnational elements of the U.S. class action is the presence of foreign class members. This phenomenon raises difficulties. What happens if the courts in the foreign class members’ home jurisdiction do not recognize U.S. class action judgments? This situation has arisen. You would then have a failure of preclusion – the foreign class member would remain free to relitigate in their home jurisdiction. This issue arose and was debated in the U.S. law review literature several years ago. There are several articles on point. For example, there is the article titled “Foreign Citizens in Transnational Class Actions” in the Cornell Law Review (2011). This issue is still alive today and I recommended it to a student this semester, with the caveat that it would need to be updated with recent cases.

Joe Gratz, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

A student asked for guidance finding a case in a foreign jurisdiction involving a mass tort with international plaintiffs. The case I recommended was in the UK Court of Appeal, Jalla v. Shell International Trading, [2021] EWCA Civ 1389. This was a representative proceeding on behalf of more than 28,000 members of the Bonga Community of Nigeria who sought to recover for harm caused by a major oil spill.

In Canada class actions are a matter of provincial law. For example, Ontario has its Class Proceedings Act, 1992. This can be used as a search term to find cases on point on CanLII. There is a recent textbook on class actions in Canada: The Class Actions Handbook (LexisNexis Canada 2022). Australia too has an active class actions scene. Class actions are governed by part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act. A recent secondary source on point is The Australian Class Action: a 30-year Perspective (Federation Press 2023).

In the non-common-law world a significant recent development is an enactment of the European Union: Directive 2020/1828 on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers. Researching class actions in the non-common-law jurisdictions encounters the language obstacle. The Netherlands for example is an active class action jurisdiction, but the primary-source information about legislation and cases is in Dutch. A partial solution to the language obstacle will be found in English discussions of class actions in foreign jurisdictions found on the Web written by international law firms.

A note of caution: a student came to me looking for class action cases in Europe in which the plaintiffs prevailed. I had to point out to him that the EU directive dates from 2020 and that it is still being implemented in member states. While it is true that Europe is an active forum for class actions, it is difficult to track cases, due in part to the language obstacle.

It’s

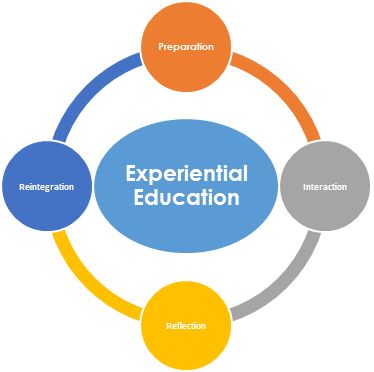

It’s  LL.M. students face a challenge that is more daunting than the one our J.D. students face; their knowledge of their own legal systems and legal publications interferes with their learning of ours. Indeed, it is something like learning another language. At the beginning, it’s like doing a puzzle in which all the pieces fit. You learn it at this stage by comparing the foreign language to your own language. At the intermediate stage, the two languages are no longer always comparable. A lot of pieces of the puzzle don’t fit any more and it’s confusing. At the advanced stage students don’t compare the languages anymore. The foreign language has become separate from the native language. Using it is now unconscious.

LL.M. students face a challenge that is more daunting than the one our J.D. students face; their knowledge of their own legal systems and legal publications interferes with their learning of ours. Indeed, it is something like learning another language. At the beginning, it’s like doing a puzzle in which all the pieces fit. You learn it at this stage by comparing the foreign language to your own language. At the intermediate stage, the two languages are no longer always comparable. A lot of pieces of the puzzle don’t fit any more and it’s confusing. At the advanced stage students don’t compare the languages anymore. The foreign language has become separate from the native language. Using it is now unconscious.